This is part 2 of a series of posts about refactoring a large TypeScript codebase. If you haven’t read part 1 yet, you can find it here.

How NOT to do it

As mentioned before, I had already done a large-scale refactor of Z-Wave JS in the past. At the time, I did actually do a lot of it by hand. I had a little help though from VSCode’s search-and-replace functionality. This works fine for replacing simple occurences, e.g. replacing new BasicCC(driver, { with new BasicCC({.

However, Z-Wave JS supports lots of different command classes, each with several subclasses, many of which are used throughout the codebase. The above simple replacement would have to be repeated tens if not hundreds of times with different class names.

At the time I also migrated from Jest to AVA for testing (don’t remember why, but something about Jest was annoying me). Both frameworks have a slightly different syntax for test assertions:

// Jest

expect(foo).toBe(bar);

expect(foo).toDeepEqual({

a: 1,

b: 2,

});

// AVA

t.is(foo, bar);

t.deepEqual(foo, {

a: 1,

b: 2,

});

Rewriting those would also have to account for different nesting levels. Also, my formatter is forcing lines to stay within 80 characters width, so the same code may look differently depending on the nesting level.

Enter every programmer’s favorite tool: regular expressions!

And boy, did I write some cursed ones…

The simple single-line replacements were fine:

expect\(([^)]+)\)\.toBe\(([^)]+)\); ⟶ t.is($1, $2);

For the multi-line ones I had to account for the nesting level, so the match would start at the beginning of the line, match the white-space and back-reference it for the closing braces. This was necessary to be able to match nested and function calls, without matching too much. Something like this:

Search:

^(\s*)expect\(([^)]+)\)\.toDeepEqual\((\{(?:\n\1\s+)+\n\1\})\);

Replace with:

$1t.deepEqual($2, $3);

…and this is one of the simpler ones.

Let the computer do the work

This time around, I decided to do things differently. Nowadays, many development tools help migrate codebases to new versions with breaking changes by providing codemods. These are scripts that automatically refactor code according to a set of rules. They parse the code into an abstract syntax tree (a structured representation of the code as nested nodes), modify that, and then turn it back into code. The nice thing about this is that we don’t have to care about formatting or indentation. These things don’t exist in the AST - at least not directly.

A popular one is jscodeshift by Facebook. If it’s good enough for them, surely it’s good enough for me!

However I wasn’t really satisfied with it. The documentation is lacking examples, and I couldn’t figure out an easy way to know how the code was represented internally - you know - to write the actual transformations. It also seemed to be more focused on JavaScript than TypeScript. For example, it couldn’t represent the difference between these two statements:

import type { Foo } from "bar";

import { type Foo } from "bar";

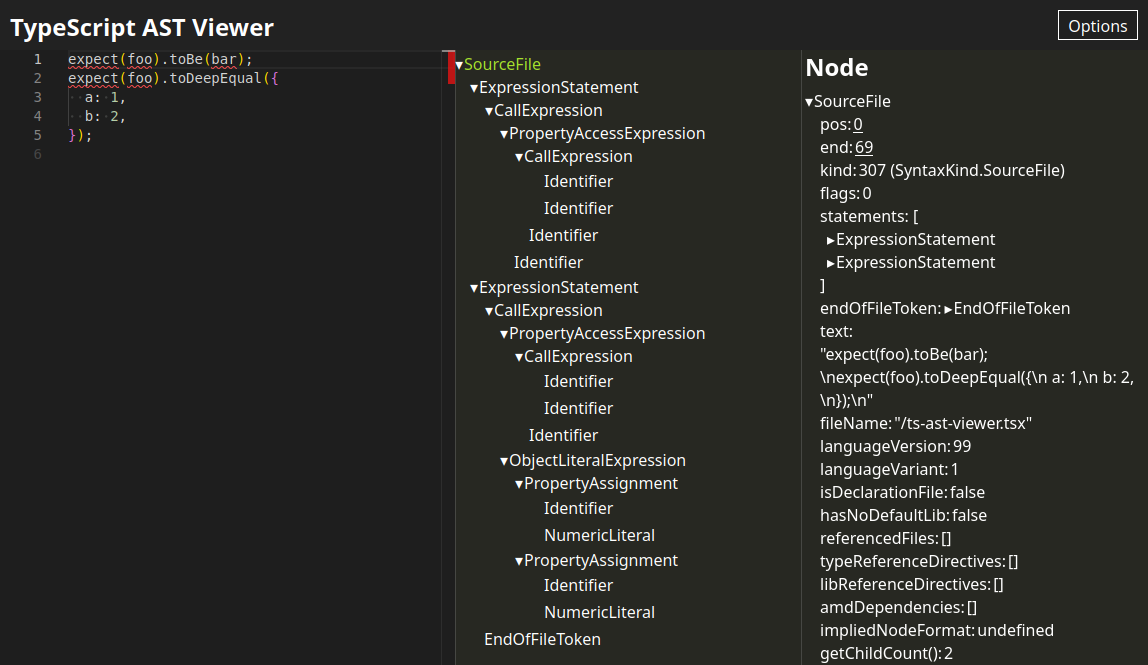

I could use TypeScript’s own compiler API to parse and modify the code. There’s a nifty tool called TypeScript AST Viewer where you can paste code and get the exact representation of it in TypeScript’s internal AST format:

It even outputs the TypeScript code needed to generate the AST. For the AVA test code above

t.is(foo, bar);

t.deepEqual(foo, {

a: 1,

b: 2,

});

this is the code to create the corresponding AST. Updating an existing one will look very similar:

[

factory.createExpressionStatement(

factory.createCallExpression(

factory.createPropertyAccessExpression(

factory.createIdentifier("t"),

factory.createIdentifier("is")

),

undefined,

[factory.createIdentifier("foo"), factory.createIdentifier("bar")]

)

),

factory.createExpressionStatement(

factory.createCallExpression(

factory.createPropertyAccessExpression(

factory.createIdentifier("t"),

factory.createIdentifier("deepEqual")

),

undefined,

[

factory.createIdentifier("foo"),

factory.createObjectLiteralExpression(

[

factory.createPropertyAssignment(

factory.createIdentifier("a"),

factory.createNumericLiteral("1")

),

factory.createPropertyAssignment(

factory.createIdentifier("b"),

factory.createNumericLiteral("2")

),

],

true

),

]

)

),

];

Guess now you know why I’m not using TypeScript directly for this.

ts-morph to the rescue!

I took a step back and realized that I’m already using the perfect tool for the job: ts-morph - a wrapper around TypeScript with a much more intuitive API. And it has good documentation!

I’ve been using it to analyze TypeScript code and generate parts of Z-Wave JS’s documentation from it. Why not use the same tool to refactor the codebase?

And so I did. Look at an easy example:

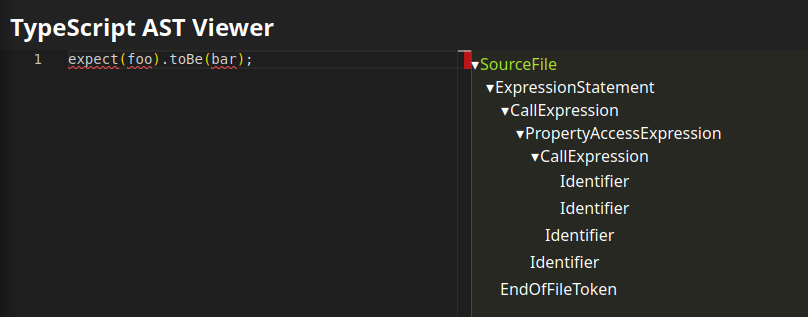

expect(foo).toBe(bar);

We want to find the two arguments for the expect and the toBe call and generate new code that uses them. A quick look into the AST viewer

reveals this structure (this requires some getting used to):

So given a SourceFile, what we’re trying to find is:

- a

CallExpressionwhose expression matches the textexpect - whose parent is a

PropertyAccessExpressionwith nametoBe(or some other assertion function) - whose parent is another

CallExpression

This can be done roughly like this:

const expectCalls = sourceFile

// Find ALL CallExpressions in the source file

.getDescendantsOfKind(SyntaxKind.CallExpression)

// Keep only calls to `expect(...)`

.filter((call) => call.getExpression().getText() === "expect")

// Keep only those

.filter((call) =>

call

// whose parent is a PropertyAccessExpression

.getParentIfKind(SyntaxKind.PropertyAccessExpression)

// that has a parent

?.getParent()

// which is a CallExpression

?.isKind(SyntaxKind.CallExpression)

);

Now we have an array of the calls we want to rewrite. We can now loop through all of them and extract the arguments:

for (const expectCall of expectCalls) {

// Take the argument to `expect(...)`

const expectArg = expectCall.getArguments()[0];

// Get a reference to the property access node. This makes the next steps easier.

// We've tested before that this node exists and is a PropertyAccessExpression

// so we use `...OrThrow` to avoid dealing with `undefined`

const propertyAccess = expectCall.getParentIfKindOrThrow(

SyntaxKind.PropertyAccessExpression

);

// Get the name of the assertion function - we might use that for generating different

// assertion functions based on this

const assertion = propertyAccess.getName();

// Get the parent of the property access node. This is the assertion call.

// Again we know that this exists and is a CallExpression, so we use `...OrThrow`

const assertionCall = propertyAccess.getParentIfKindOrThrow(

SyntaxKind.CallExpression

);

// Get the argument to the assertion call

const assertionArg = assertionCall.getArguments()[0];

// TODO: replace with new code

}

Remember the TypeScript code I showed above on how to generate the new AST? The corresponding code for t.is(foo, bar); would look like this

factory.createCallExpression(

factory.createPropertyAccessExpression(

factory.createIdentifier("t"),

factory.createIdentifier("is")

),

undefined,

[factory.createIdentifier("foo"), factory.createIdentifier("bar")]

);

…except that instead of creating the identifiers foo and bar, we’d reuse what we found in the original AST. Pretty awkward.

Want to see how to replace the call expression with ts-morph?

expectCall.replaceWithText(

`t.is(${expectArg.getText()}, ${assertionArg.getText()});`

);

Yes. Text. ts-morph figures out the correct AST for you.

As the last step, save the source file and the code transformation is done:

await sourceFile.save();

By the way, this transformation would also have worked if the test code was more complex, like

expect(

myMethod({

option1: true,

})

).toBe({

a: 1,

b: 2,

c: {

d: 3,

},

});

Final words

Transforming code automatically can get pretty complex - I’ve collected several files with a couple hundred lines of transformation code, handling multiple edge cases. But this pales in comparison with the tens of thousands of changed lines across hundreds of files it generated. Here’s just one PR as an example:

And this was super easy to iterate on. Run the transformation, check the git diff. If something was not transformed correctly, undo the changes and repeat.

Imagine doing that with RegExp!